Spaces for Wellbeing in Higher Education

Lyndsey Housden, one of the participants of Interdisciplinary Research Group (IRG) 2021-2022, reflects on her research process at the IRG and how this journey has influenced both her own artistic practice as well as her pedagogy practice at the KABK.

Introduction

Context of the research

We were approaching the end of the coronavirus lockdown and I was moved by the collective experience of that moment, as we transitioned from our lockdown habitats of personal space and private routines, into public space and time. The new, old way of life that we were gradually returning to, was calling for a physical and social presence, which had become strangely unfamiliar.

The pandemic was undoubtedly a period of uncertainty and considerable loss, which is still being felt today. At the same time, the lockdown offered a rare opportunity to experience the slowing down of time and the emptying of space, as our cities and skies became quiet and still. In this pivotal moment, as we transitioned into the so called new-normal, I wondered if we would find a way to carry forward this shared experience of simplicity, self-reflection and collective contemplation.

Could this be an opportunity, for higher education to make physical space and time for the wellbeing of students, staff, teachers and other beings, within their institutional buildings?

Design research

The proposal for the Interdiscliplinary Research Group (IRG) 2021, started out as design research into the potential for spiritual spaces within higher education, with a focus on the Royal Academy of Art (KABK). I was interested in the concepts and methods in music composition, that transcend the consciousness beyond the day-to-day reality, which might be applied to spatial design. This is elaborated further in the text below. This focus shifted to spaces for wellbeing within in higher education, as I recognised the need for a term that was inclusive in its practices and tools. To consider new facility within the institution that could speak to a diverse and evolving community, to support mental (and somatic) health, personal development, and embodiment practices. A facility to offer tools and encourage autonomy, community building, rest, and much more. The focus of this research, therefore shifted into an investigation into the architecture of the KABK and its potential to offer space for wellness.

The IRG 2021 has supported two outcomes that are described in detail below, together with an explorative (and ongoing) research on a space for wellbeing at the KABK. One outcome was the development of an Inter-departmental course for KABK second year Interactive Media Design (I/M/D) and Interior Architecture and Furniture Design (IAMO) students, which will begin in January 2023. The course was developed in collaboration with architect and educator Pauline Bremmer, where we aim to investigate the architectural conditions of interdisciplinary learning. The second outcome is a sound work titled Embodied Observation #01 (EO#1), which is available on this platform. EO#1 is a simple practice that aims to prepare the mind-body to let go of pre-conceived ideas or habits, pausing these expectations to stimulate the possibility of new perspectives and possibilities when looking to bring change or renewal to a space.

The emerging reality of situated design research

The IRG offered an opportunity to explore a long-term fascination and interest in my art practice, in the relationship between music composition and spatial design. I proposed that concepts in music composition, might offer valuable insights and tools to the spatial imaginary, for the composition of atmospheres and the affordances of spatial design for wellbeing. Atmosphere is a vital design component in architecture and is often created by subtle, non-visual aspects of design, that engage multiple senses, offer multiple viewpoints or perspectives, and often use natural elements of light (and heat through sunlight), water through reflections or flowing spatial dynamics, and natural materials. One example of how space can easily suggest an atmosphere is through the design of acoustics. Whereas an experience of privacy or intimacy can be fostered through sound absorbing materials, to soften and quieten the reverberation of (your) presence, thus suggesting stillness and reducing distraction, to facilitate introversion or quietness. Conversely when (your) movement is projected and reflected off the walls of a space, the impulse to sing, project and play with the spatial acoustics - such as is often the experience of teaching in the extremely reverberant space of Gallery 3 at the KABK, (your) presence, and everyone else in the space, becomes unavoidably public and performative, extrovert and often unavoidably loud and chaotic. I was interested in the ability of music to affect the listener intuitively in ways that often lead to a meditative state of mind. I started to explore the relationship between architecture and music, to investigate how techniques in music composition might be transposed to spatial design.

Could this approach for example, lead to atmospheres and environments that support stillness without guidance or explicit rules, simply through the affordance of the spatial design?

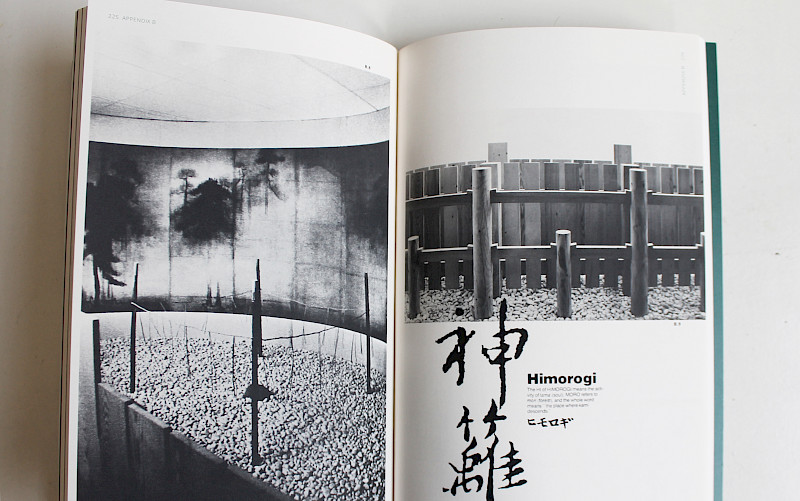

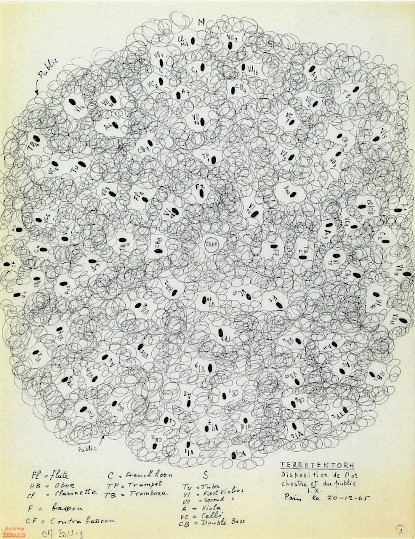

One of the masters of composition in time and space was Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001). The Romanian-born Greek-French avant-garde composer, music theorist, architect, performance director and engineer, who after decades of mathematical engineering understood intuitively the affective relationships between geometry, scale and matter, in both his architectural designs and music compositions. In this pre-digital era, it was remarkable how he used the same creative methodologies based on mathematical formulas in his architecture and music. Looking at Xenakis’s compositional drawings and scores, for example as seen in the image 1234 - study for Terretektorh (distribution of musicians) from 1965, it becomes clear that the spatial arrangement of musicians on stage, and in some cases the positioning of the audience within the performance space, was a direct translation of Xenakis’s architecture sensibility into musical expression.

I.Xenakis, 1234 - Study for Terretektorh, Iannis Xenakis Archives,

Bibliotheque nationale France, Paris, 1965

In the IRG meeting of March 2021, we listed to Nekuia, written by Xenakis in 1981. An incredible work for 89 musicians and 80 voices, which incorporates phonemic text and extracts from Siebenkäs by Jean-Paul Richter. An excerpt from the record sleeve text, of the out of print recording reads “… the general idea of this music is the profound cry of the ideologies crossing the surface of our planet, often to the noises of street demonstrations, explosions and shouts, under a sky that is sometimes dark, but sometimes of a splendid azure.” [1]

Listening in stereo on domestic speakers, by no means satisfies the sublime, spatial experience created by 80 live voices and 89 live instruments, densely compressed onto the stage of the Concertgebouw theatre in Amsterdam, where I was fortunate to experience in 2011. A total of 169 voices and instruments were engineered to create a sonic environment, one that seemed to embody every frequency of audible sound. Projecting, reflecting and dissipating the composition, as it morphed with sculptural precision through the body of the concert hall and its audience members. Distinct atmospheres of sonic energy, like thermal currents conducted through a void. Music on this scale could only have been imagined by an architect.

In May 2021, the concept of architectural spaces for wellbeing within higher education was becoming more urgent. The many changes and transformations within the KABK over the last year were beginning to settle. The open questions that remained for the KABK searched for ideas that could help contribute to creating a healthy community, with a sense of belonging and safety. I decided to place the research into spatial design and music composition on hold, to focus on the needs of a learning community, on a space for wellbeing. I was reminded by a colleague during an online training, who expressed in exhaustion, ‘guys, i’m so sorry, I need to sit out today, I just need silence’. An honest expression that struck a chord with many in that virtual room. I began to research existing spaces for wellness within international higher education and universities. I was encouraged to find several examples of existing and soon to be opened wellbeing centres. Although mainly in the US, these references offer inspiration and examples of how to position wellbeing facilities and services within learning communities. These carefully designed spaces in some cases also included an educational curriculum that bridged traditional programmes with consciousness studies, hosted in Contemplation Centres. These are a few examples:

The Monash Centre for Consciousness and Contemplative Studies, based at the Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, was established in 2021 to “[enable] multidisciplinary humanities, psychology, medicine and neuroscience research at the forefront of consciousness science and contemplative studies. It applies philosophical and scientific rigour to provide profound, new answers about the very essence of consciousness and contemplation, demonstrating their role in our lives, for wellbeing, and for future generations.”[2]

Another example is the Contemplative Resource Centre at Colorado University, smaller in scale and created as an extra curricular facility, to provide space for meditation and contemplation practices, as well as ‘embodied experience to support holistic health and wellbeing’ welcoming all members of its learning community. [3]

Aidlin Darling Design, designed both the Contemplative Sciences Centre at the University of Virginia, in collaboration with UVA office of Architecture, and the Windhover Contemplative Centre at Stanford University, US. The Contemplative Sciences Centre, at the University of Virginia is due for completion in 2023 and proposes a wholistic vision for Contemplative Commons, a centre for Transformative Learning that incorporates customisable studios, and an architecture that transitions from inside to outside, to foster academic innovation, and personal and social well-being.

The Windhover Contemplative Centre at Stanford University (USA), Designed in collaboration with Andrea Cochran Landscape Architecture, is a ‘spiritual retreat' on the Stanford campus, with “rammed earth walls, wood surfaces, and water [to] heighten the visitor's sensory experience acoustically, tactilely, olfactorily, and visually." [4]

Why wellbeing? Another buzz word or…?

Wellbeing is described by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention as “a positive outcome that is meaningful for people and for many sectors of society, because it tells us that people perceive that their lives are going well”. [5] In 2018, Henning et al. state in the introduction to their book on Wellbeing in Higher Education, that “…integral to the sustenance of wellbeing within higher education settings, [is the promotion of…] healthy learning environments for both higher education staff and students. The synthesis of these ideas is crucial to the understanding of higher education as not only an environment for gaining academic and career knowledge but also an environment for developing human and social skills that will assist students later as valuable participants of, and contributors to, the professional communities that they serve.” [6] Here the editors acknowledge the valuable tools and experiences that students and faculty members gain to understand how to maintain their health and wellbeing within high pressured (academic) environments, the authors consider the responsibilities of work and learning institutes to prevent or reduce the common symptoms of such environments such as over work, stress, burn out, or long term chronic health conditions and diseases, which may develop when the complications of stress and work pressure remain low priority and unchecked.

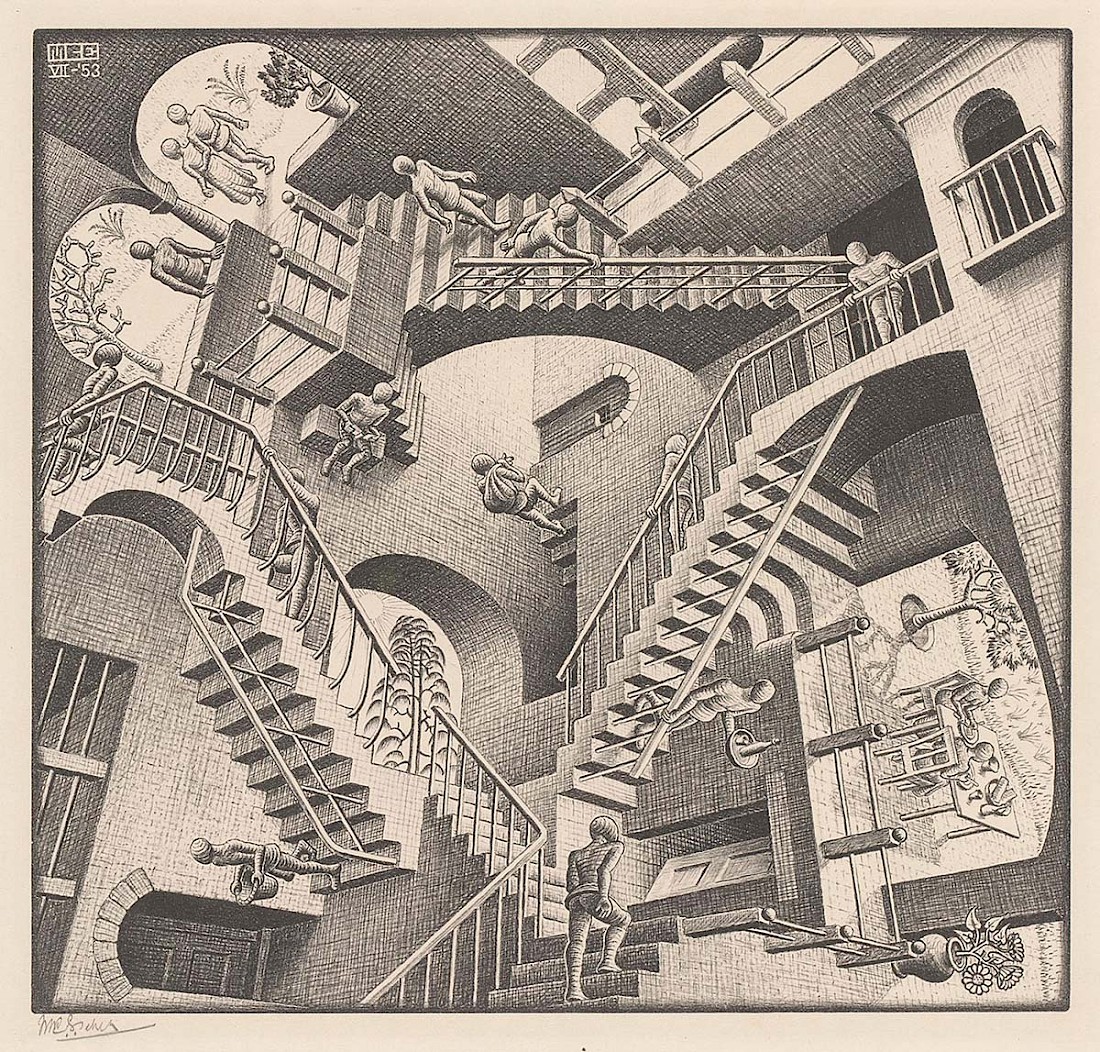

In June 2021, walking through the monumental building of the KABK, where I teach at the Interactive/Design/Media department, ones vision unfolds endlessly across the reflective hard surfaces, tiled staircases and corridors. The image of ‘Relativity’ (1953), by the Dutch artist M. C. Escher comes to mind and incidentally can be viewed a few streets away, at The Escher Museum, Het Paleis.

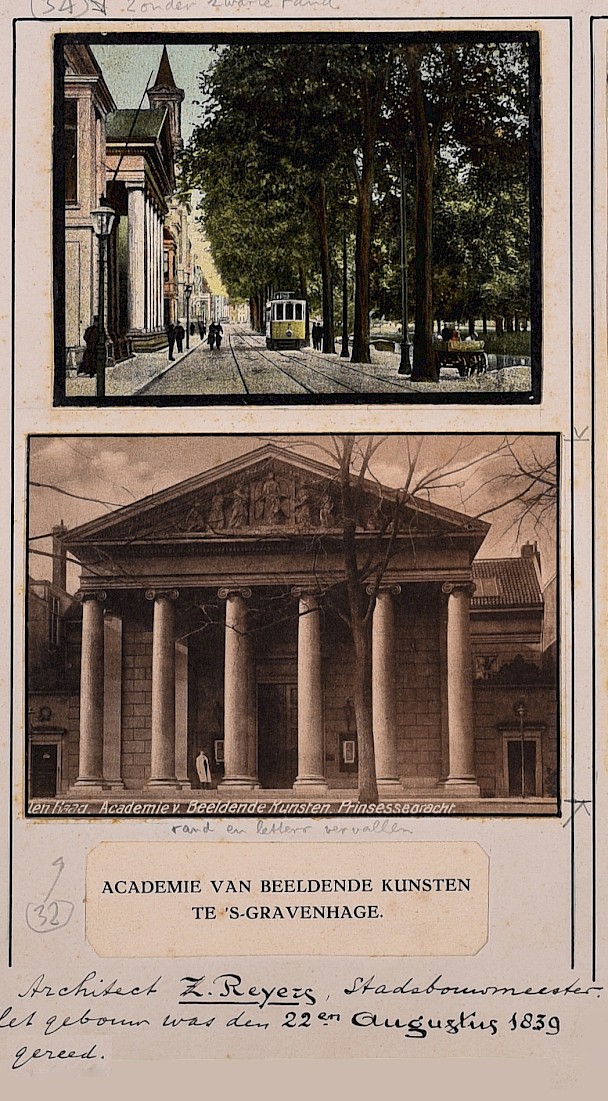

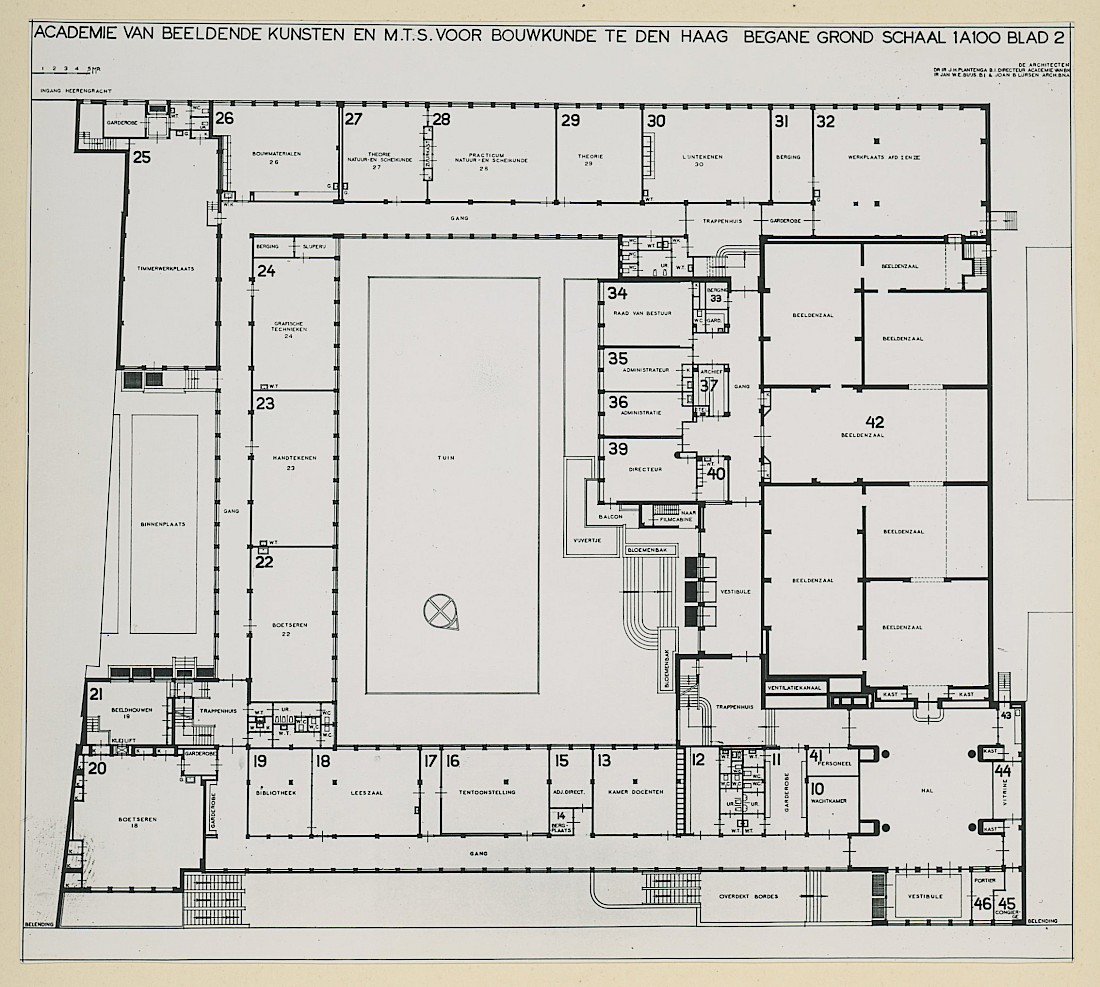

The KABK building has developed over the centuries along with the needs of its community and the contemporary culture of the time. Moving through neoclassical columns of the original Prinsessegracht building, built in 1839 and designed by The Hague city architect Zeger Reyers. Demolished just 100 years later and reconstructed between1934-1937 into a new design by KABK director and architect dr. ir. JH Plantenga. This building, which still stands today at Prinsengracht 4, was envisioned to facilitate a modern, Bauhaus influenced art and design education, bringing together art, design and craft into one academy. With its lucid NW facing windows, filtering north sea light into the painting studios, we see the organisation of art and design disciplines positioned in discrete departments, subsequently forming the organisation of the building, the community and the curriculum. A legacy that still operates today.

In the year 2000 the building took on yet a new form, expanding horizontally by connecting with the former girls school of the now Blijenburg building, and vertically through the addition of an extra floor, a transparent glasshouse structure on the roof of the Prinsengracht 4. This architectural development was intended to end the separate, temporary buildings and external sites, which were scattered across the city to accommodate the expanding curriculum and student body. The UNILOCATIE project was designed by Van Mourik Architects and completed in 2000, aimed to reconnect all the departments together under one roof.

Spatial design for wellbeing

I was looking for a concept that might guide my search for a suitable location, I researched further into the architectural theory of Kengo Kuma, who was responsible for the meditation space Wood/Pile in Das Kranzbach Resort, Germany, as mentioned earlier. In his book Anti-Object, Kuma offers a compelling criticism on the effect of modernist architecture in separating the architectural object from its environment. Kuma reflects on the connections between the scientific (Western) way of thinking developed during the Enlightenment period by Descartes and Bacon and the separation of architecture from its environment. Kuma writes, “…to be precise, object is a form of material existence distinct from its immediate environment.” and he goes on to say,“[7] even twentieth-century modernism, which ostensibly strove for transparency and openness, was deeply tainted by the disease of objectification. Indeed, objectification might be said to be the very strategy by which modernism succeeded in conquering the world”.

In Kuma’s designs we can see a deep desire to reconnect object and environment, through an architecture that is aware of the interdependency with its environment, as part of nature. His use of locally available materials in his design for the Wood/ Pile meditation centre in Germany, intended to achieve a continuum between the inside and outside, architecture and environment. He describes the choice of material: “…[F]ir trees grown near the site and milled […] to a width of 30mm, piling them up like twigs, in order to produce a transitional scale between the large forest and small architecture. This is also a medium through which humans can be integrated into the forest. The little twigs disperse the light filtering through the skylight, repeating the effect of komorebi or ‘rays of light’ often experienced in the forest.[8]

When considering the conditions for wellbeing spaces, which facilitate practices and tools, such as meditation, mindfulness and the many embodied practices, which aim to address the sense of separation inherited through Cartesian dualism, I am reminded of the contemporary, fractured experience of time and space. Here Kuma draws our attention to modernisms attempt to also create a separation between time and space, he states: “[W]e have become so accustomed to perceiving space and time as separate things that we forget this is the fundamental nature of the world, and even feel the connection of time and space be a contradiction.”[9]

With this insight he proposes that the horizontal axis under our feet as the redeeming field of focus, for the architectural term he coins anti-object. “[T]he floor is an element belonging to both space and time. Whereas the wall is an exclusively spatial element - its presence is easily perceived at a distance and from a fixed (i.e nontemporal) viewpoint - the floor unfolds as the subject moves. It is revealed in its entirety only gradual, that is, over time. Consequently, the floor is not simply spatial but temporal in character.”[10]

He reminds us that through gravity, we are always in contact with the ground, and a floor can seamlessly move from inside to outside, to mediate our relationship in time and space, with the environment as part of nature.

Kuma’s notion of Anti-Object, as a critical reflection on modern architectures separation of object and environment, subject and the world, and temporal and spatial experience, is inspiring in relation to the needs of a space for wellness. Furthermore, his insight into the floor or ground, as a transitory plane, a perspective that is revealed through movement and physical exploration, step-by-step bringing about the feeling of being ‘back’ in the here and now, is also inspiring in relation to a space that facilitates mindfulness, and awareness.

A site for wellness at the KABK?

During many journeys around and through the KABK, there was one location that kept drawing my attention, situated both inside the academy and outside the building, the courtyard of Prinsessegracht 4 or the garden space designed by Plantenga, is one of the few locations at the KABK that is not regularly programmed or bookable (except during graduation exhibition) and it is open to all members of the community, students, staff and teachers. The largest, open space of the academy and surrounded completely by windows to corridors and classrooms, a square void of sky, living beings, plants, trees and soil, faced on all four sides by different disciplines and departments, as well as the director and staff offices.

When making a site visit for a new site specific commission, I usually have the advantage of the first impression that develops slowly over time. I become acquainted with the way the architectural site moves me, the impression it leaves when I turn away at the end of the day. A relationship evolves through listening and inhabiting the space, from day until night. Piecing together its rhythms, cycles and atmospheres. Sensing the history and untold or projected stories, as I respond or resist its affordances. What does this building want? What does it offer? What is not apparent? Where are the cracks and the humour? Where are the sublime lines of endless space that move beyond the architects page into my imagination, of a space felt but not yet seen.

With a site I know well such as the Prinsessegracht courtyard, to become reacquainted and begin this creative process, I needed a different approach, one that would enable me to unsee and unknow the Prinsessegracht Courtyard, to unfamiliarised myself with and un-inhabit the space. If I could achieve this, I would be able to explore the potential of the space, without the illusion of preconceived ideas, which may no longer be relevant. Therefore to begin this process, I consciously and explicitly enacted the process that I would typically go through during a site exploration. The intention was to later analyse this process and distill the steps to create a guide, or method, for preparing to let go of preconceived ideas and habits of a space or site you wish to renew, or bring about change.

The KABK Courtyard

The KABK Courtyard, as it stands today is the outcome of UNILOCATIE renovation in 2000. In conversation with Ernst Bergmans in June 2021, I learnt about the development of both the KABK architecture and also of the courtyard and its local myths. Bergmans, who supervised the renovation project by Van Mourik Architects in 2000, is also an avid historian and careful archivist of photos and stories, which formed over his 40 years, as part of the KABK community, as a student, staff member, teacher, interim head in almost all departments, and lastly as a key team member and fundraiser for the KABK UNILOCATIE project. Bergmans kindly shared his experiences and insights into the architectural developments over the centuries. He confirmed the purpose of the stones, of which I had received various different stories and ideas, one suggesting that the stones were remnants of local buildings destroyed in World War II, and therefore monumental and impossible to remove, a story perhaps created, I may never know. In fact the stones are former houses and buildings, rubble of demolished buildings, a pragmatic (cheap) solution for tight budget, at the end of a long renovation project. The Courtyard as it stands today was intended for use by students, to present artworks and the grid system made of concrete tiles, just seen in the photo shows areas where the art works might be placed.

Embodied Observation #01

Prelude; enactment of the first site-visit

This text is a poetic impression of this first site visit at the courtyard of the KABK, Prinsessegracht 4 The Hague. The material created from this was analysed and scripted, in preparation for the audio guide Embodied Observation #1.

It was Saturday the 29th of May 2021 and one of the first gloriously sunny days of the year. The air was warm and unfamiliar as we emerged out of the colder spring months. I brought with me an A4 sketch book, a pencil and a small digital camera. I wore clothes and shoes that I could climb in and carried a bag to collect materials. As I entered the building I made my way (albeit knowingly) towards the courtyard, and as I walked along the beige and cream tiled hallways, the sun and warmth emanating from the courtyard lead the way. I stopped at the entrance, facing the KABK-blue metal-framed courtyard doors, looking through the single-glazed glass, wall and door panels. Before moving through the entrance, I would first walk the periphery. Circling the rectilinear, window lined corridor looking from the outside in, or was it inside out? Each step, brought my mind and body closer through a rhythm that disconnected my thoughts with the intention at hand and prepared my senses for a re-impression. Each step along this non-space in-between teaching rooms, administration and management offices, toilets, and the courtyard, took me further away from what I thought knew. I became aware of the details of the environment that I was immersing myself in. Semi-consciously I began to detach from what I thought I knew, to begin the process of seeing anew, to be aware of what was actually there, around me, and not only what I thought it was named.

As I arrived, I was met with the same feeling of opening a small gate to a playground, made of a similar colour to the KABK-blue, metal door frames. The first thing that called my attention was the easily climbable wall of the garden planters. Standing on the edge of the planters, at the top of the stairs I looked down to the courtyard, and observed a few smaller (in perspective) bodies, seemingly looking for the same answer as I was. I searched for a place where I could arrive and effortlessly absorb my senses into the environment and its atmosphere. The red bench in the sun called me over, and I carefully walked over the uneven ground, with its awkward loose rubble stones, jolting my weak ankles here and there, hoping avoid a sprain, I made it to the bench and lay down.

The process that follows, leads me to follow the path of the wind, to a pile of Acacia seed husks, worn down by the North Sea wind, and pushed up against the coldest corner of the courtyard that receives the cool, fresh morning sun. The edge of the seed pile leads the eye to a KABK-blue, small metal door, with a cold steel handle. Walking down the red brick steps to the basement level, where the space behind the door occupies, I turn the handle, its tight lock invites curiosity - where does this door lead I wonder? Back up to ground level, the eye is distracted by a rolling hexagonal prism, seriously! More curious still, the surface of this white cardboard object is imprinted with the architectural floor plan of the KABK, I am not alone I think with a smile, as the untold stories begin to reveal themselves…

I notice a bright red ladybird scaling the heights of a blade of green grass. I zoom in to the ecology next to my feet, of wild plants and flowers, breaking through the nylon underlay, beneath the strange stones. Bees hum past me, uninterested in my presence, to pollinate the purple flowers, dotted between the various leaf formations.

Things begin to shine.

Squatting on the floor, my hands meet the stones. How different they are in the hand than underfoot where they act as tiny provocations to a twisted ankle. Here in the hand, they become useful and they feel different. Some are heavy, made of dense marble stone, some an amalgamation of concrete and gravel, some ceramic with a 1950s hue of light-blue, soft glaze. Some are carved with curves into a dark grey stone, some clearly worn down fragments of red brick and mortar, some rounded glass pieces with a metal grid inlay; all elements of past homes I think. So beautiful, I begin to collect the stones for possible re-use. I am reminded of the small one person meditation spaces from an ashram in Rishikesh, India (popularised by the UK pop band the Beetles, who stayed there in the late 1960’s). Perhaps these stones could be collected and used as building material for small quiet spaces I ponder, similarly they remind me of climbing grips, and I see climbing walls emerging from the interior walls of the courtyard. Gathering the last of the stones, I feel that have arrived at the end of this embodied observation.

Through the process, I have become completely immersed in the possibilities and potentials of the site. I felt, observed, and was guided by the affordances of the space, aspects that I had not experienced before and accepted the gifts they offered. I leave with questions about the stones, where had they come from and could they be reused? The plant life, supporting insects and bees, pollinating and making home in the mini-ecology that has sprung-up through a thick woven sheet, sealing the soil. The small, KABK-blue door proposes to lead somewhere, but where? Lastly, observing the sharp form of the academy’s shadow as it casts the time of day, moving with certainty across the courtyard and directing me to an area that might offer potential, as a location for wellbeing. Whilst this area is the coolest corner of the courtyard, it offers the crisp morning light to set the biorhythms of the day into sync, and provides a cool space in those hectic and heated summer months.

I return back to the red bench, regaining contact with preconceived knowledge of the site, and my appetite. I have lunch, then turn to the space to thank it for cooperation, and exit through the KABK-blue, metal-framed doors, back along the cream and beige tiled corridors, and out into the city.

Embodied Observation #01 - the audio guide

This audio guide was written and developed in conversation with the IRG members during a work-in-progress presentation on 6th July 2021. The IRG session #7, as with all IRG meetings was hosted online in Teams, I presented the research-in-progress of Embodied Observation from the vacant directors office, and simultaneously from the Prinsessegracht courtyard. It was a first attempt to reflect on, and make explicit the embodied creative and research process I use in the research of a site-specific artwork.

The intention was to generate a guide to prepare the mind-body for the site-specific creative research process. Embodied Observation #01 is aimed to support a process of letting go, of preconceived ideas and impressions of a familiar place. Notions and expectations, which are stored in the memory due to a relationship with the space, and / or a role in its community. Notions that generate convenient habits, patterns of behaviour and subconscious thought processes. This guided practice is intended to support the process of letting go of these expectations, stimulating new perspectives and possibilities. The tracks are intended to be followed in sequence and can be paused, or repeated at any time.

This audio guide is presented as research-in-progress, and comments and iterations are welcome. Before you dive into the audio guide yourself, I would like to take some points into account:

- The total time required for the practice is dependent on your creative process.

- Each track is a sign post, to initiate each phase of Embodied Observation #01.

- Your creative process is made in silence - the tracks provide an impulse to begin each phase.

- Feel free to pause at any time explore in silence, access your imagination without interference.

- The actions of each phase could include movement, observation, listening, documentation, touching, collecting, all according to your creative process.

Outcome of the Research

KABK Course Interdiscliplinary Spaces

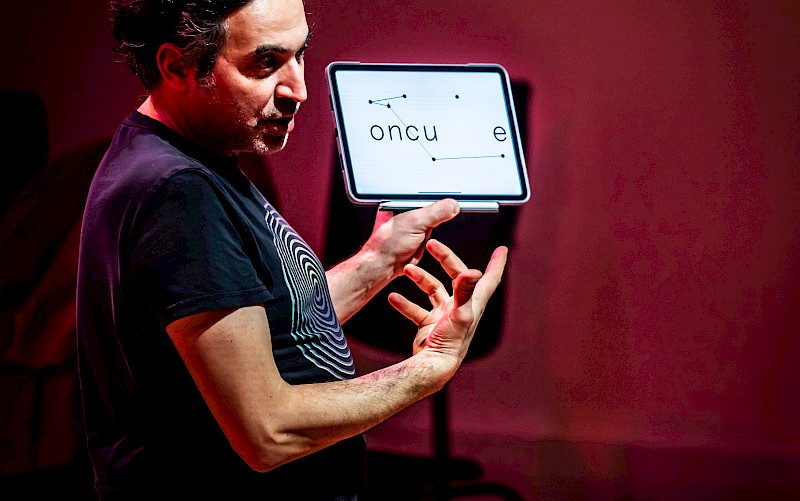

Interdiscliplinary Spaces, an interdepartmental course with second year students from Interactive Media Design and Interior Architecture and Furniture Design (IAMO), starting in January 2023 until June 2023, led by Pauline Bremmer, Aref Dashti and myself. The concept of the course was developed during the IRG, in collaboration with architect and educator Pauline Bremmer, who led an interdisciplinary team of students, staff and teachers at the Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam in co-designing the extension of the Academy. In her website, Bremmer writes: “The central idea in the conception of the design was the strengthening of collective space. To work, educate, make and learn in a more interdisciplinary way, the new building is seen as an opportunity to foresee in this hybrid environment.”[11]

During our conversations and writing sessions, in De Wittenplaats broedplaats in Amsterdam, where we both had studio in 2021, we developed a research proposal and concept of the course, where we will research the architectural conditions and best (spatial design) practices for learning environments, that nurture and stimulate, interdisciplinary, collaborative and collective learning communities. The research is situated within the KABK and focusses on student-led, interdisciplinary and informal spaces through a collaboration with students, teachers and staff at the KABK. The research is prompted by an observed increased need, for student-led, adaptable and flexible learning environments at the KABK. Spaces that are responsive to the conditions and needs of education in today’s unpredictable, virtual, hybrid and diverse society. Underpinning the motivation for the research project is a search for a reconnection between pedagogy and topology - for an educational architecture that is based upon an open system, a living ecology that is inherently in a state of transformation, where all elements of the educational environment are transparent and in support of a creative learning community. The course proposes to research and develop design concepts through 1:1 scale prototypes, architectural interventions and actions, which will be open to all.

As we move towards the end of another 100 year cycle since the last architectural reconstruction, lead by Plantenga in 1934, the international community of the KABK is looking now again at the architecture of the KABK and its conception as a system of departments, which create an organisation and infrastructure with distinct disciplines, with their own cultures, practices and techniques. Over the last 100 years, we have seen an incredible increase in the availability of tools, technology and travel. These instruments of creation, design, communication and mobility are fully integrated into the present day KABK learning community, local and international environment. These resources are either privately owned or a shared as a resource of the KABK through the workshops, labs and equipment rental, extending the classrooms into the students private spaces through hybrid learning and online teaching, which was forcefully developed and gradually adapted during the pandemic, as we recognised the advantages of reduced travel and quiet work spaces. Every aspect of the present KABK culture, its epistemologies, values, relationally, diversity and positioning, are evolving within a digitally connected, hybrid, virtual network of students, teachers, alumni, professionals, and in dialogue with the pressing questions of our time, which pull us out of the studio and classroom, and into the streets and onto the internet....,

reminding me again of the description on the record sleeve of Xenakis’ Nekuia from 1981.

Sources

[1] Xenakis - Nekuia (1981) – out of Print Recording, www.youtube.com/watch?v=2_Txie4lAMk&ab_channel=newmusicMB [Accessed 4 Dec. 2022].

[2] Monash Centre for Consciousness and Contemplative Studies (M3CS), https://www.monash.edu/consciousness-contemplative-studies/about[Accessed 8 June 2021].

[3] What is Contemplative Practice? | Contemplative Resource Center | University of Colorado Boulder, https://www.colorado.edu/center/contemplativeresource/what-contemplative-practice. [Accessed 8 June 2021].

[4] About Windhover | Office for Religious & Spiritual Life, Link [Accessed 8 June 2021].

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, October 31). Well-Being Concepts. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, [Accessed 4 December 2021].

[6] Henning, M.A., Krägeloh, C.U., Dryer, R., Moir, F., Billington, R. and Hill, A.G. (2018). Wellbeing in Higher Education. Routledge.

[7] Kengo Kuma and Architectural Association, Anti-object : the dissolution and disintegration of architecture. London: Architectural Association, Great Britain, 2008.

[8] ibid

[9] ibid

[10] ibid

[11] Bremmer, P. Interdiscliplinary Spaces, research proposal, 29 November 2021