Experimental Research 'In the beginning...'

'In the beginning...' is a narrative-based, experimental research project by Georgie Brinkman about a colony of tardigrades who crash-landed on the moon. She shares 'The Great Cosmic Other; an essay on research as sense-making'.

Tardigrades beyond the aether

Written by Georgie Brinkman

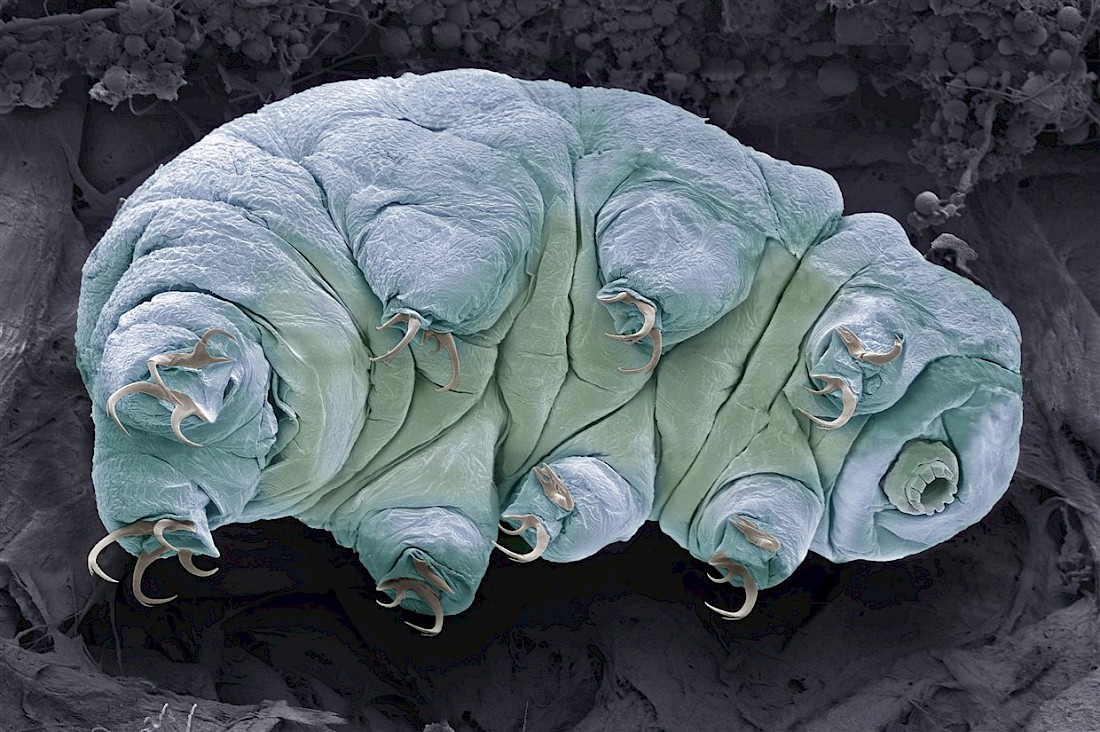

Cast your mind way back to pre-pandemic times, late 2019. It was in this time that I was invited to work on a commission with SHOAL, a new music collective based in Manchester. Amongst other female artists I was asked to respond to one of the four aethers — earth — to devise a performance with SHOAL. I brought to our first workshop the proposal of working with tardigrades, tiny eight-legged animals that dwell in the earth, all over the Earth.

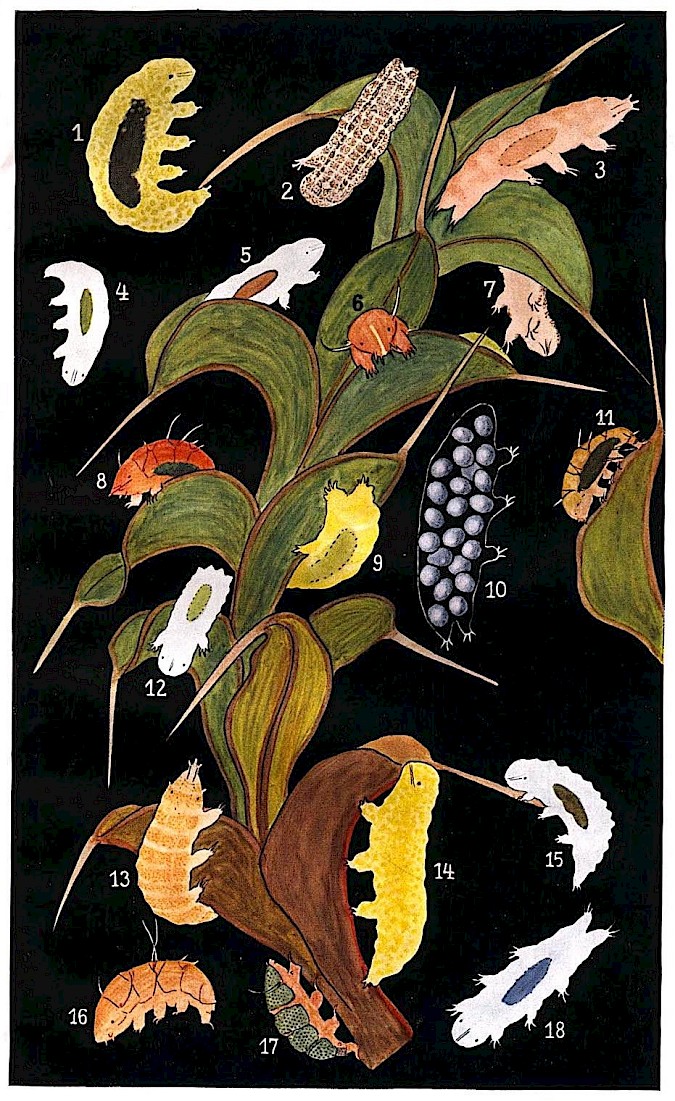

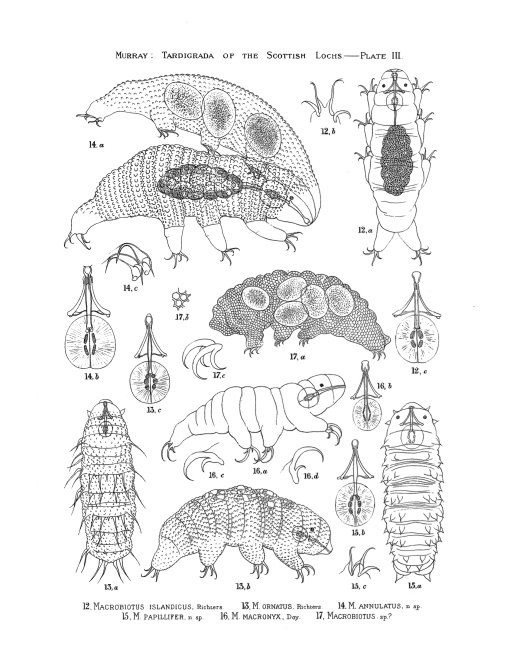

During our workshop, we ruminated on human perceptions of the underworld as a mystical, if somewhat dangerous place, and how this impacts on our perception of creatures who live underground or in the undergrowth, such as tardigrades. How we make sense of the things we cannot see with our eyes. We soon landed at the term chthonic. In Greek mythology, those related to the earth and the underworld are termed chthonic, with the most famous chthonic deities being Hades and Persephone. We wondered why chthonic deities so often took human form. Why don’t deities resemble the creatures who reside there, like ants or worms? We imagined tardigrades as chthonic goddesses, fantasised about them being the early basis of Mother Earth religions. What if ancient humans had known about tardigrade existence before they were “discovered” under a microscope? They had somehow sensed it, their existence. And could tardigrades be contenders for a new, other-than-human spiritual guide today? After all, their near-magic abilities to survive extremities seems to be something to revere.

But how to revere a tardigrade…

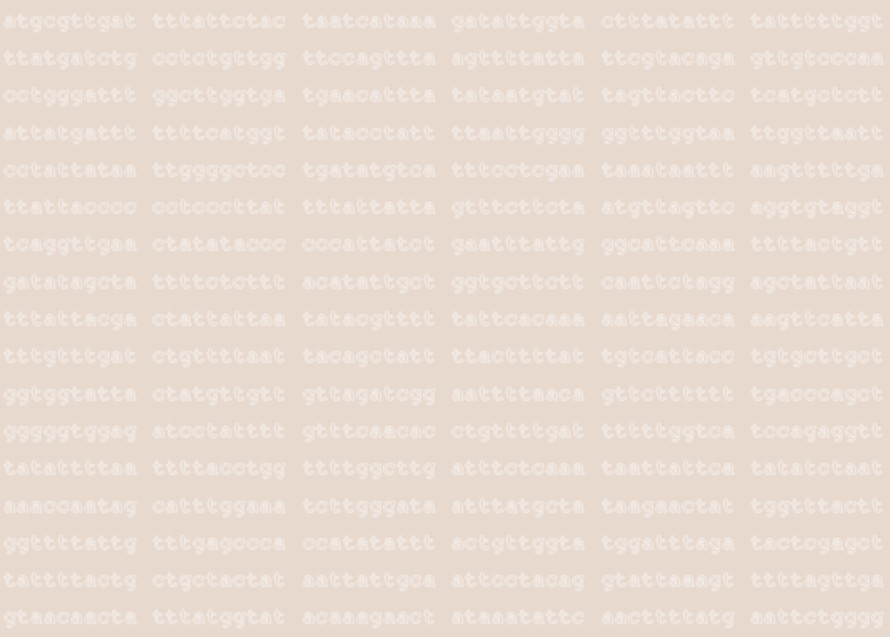

What is an essence, the aura, the fundamental makeup of something, or someone? In the scientific era we live in, it can be argued that this is our DNA or genome. Our genetic makeup is what fundamentally makes us up. If a mortal being were to be considered a deity today, does this mean that we would worship their DNA?

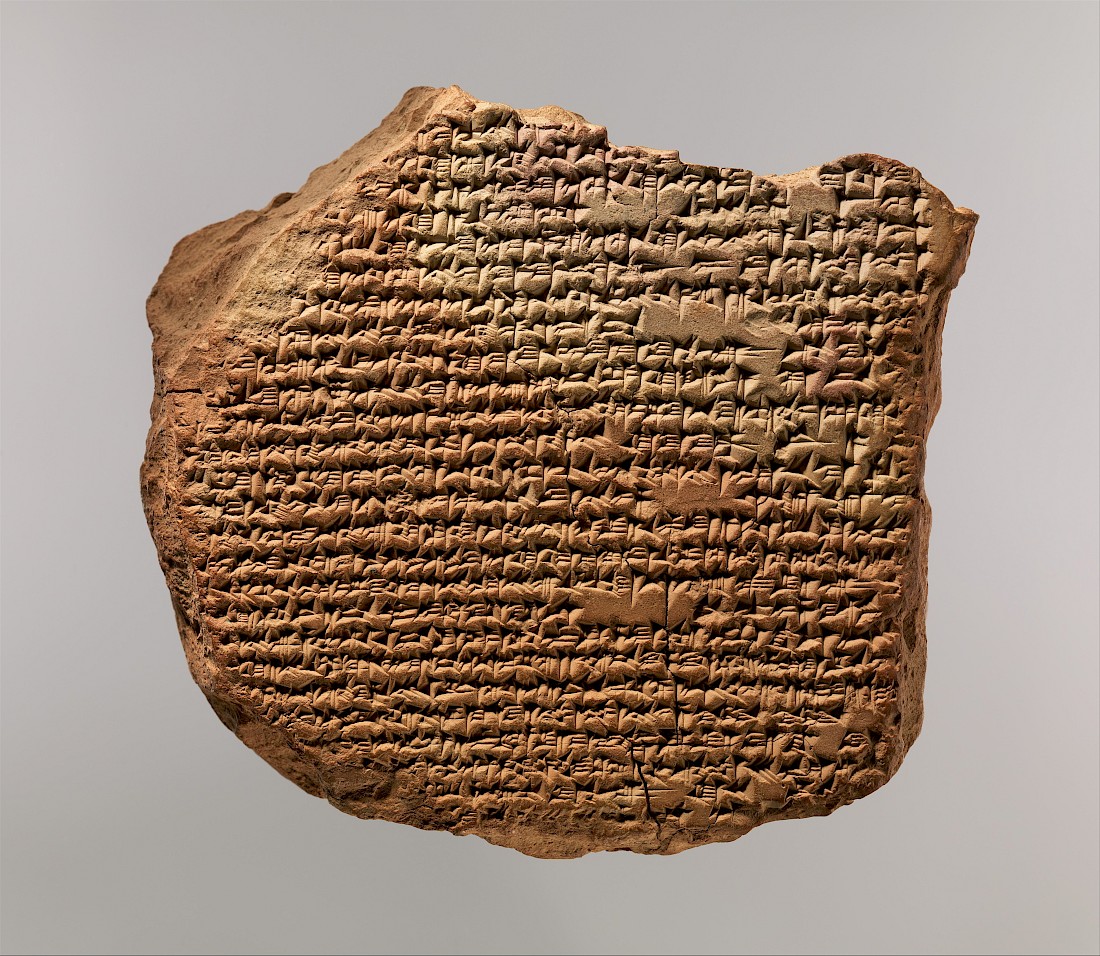

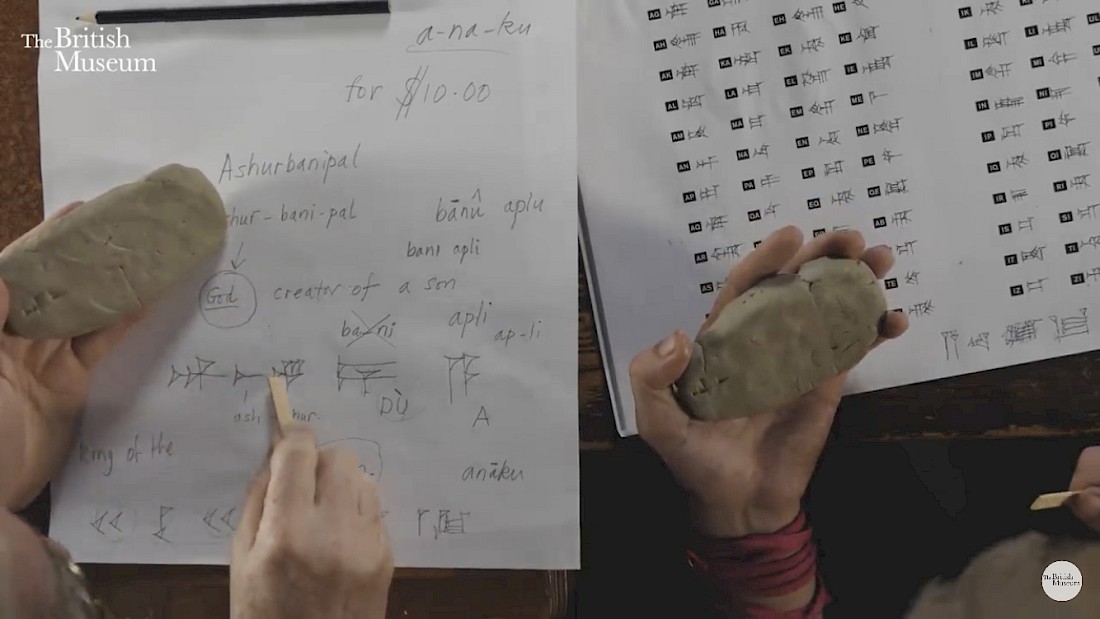

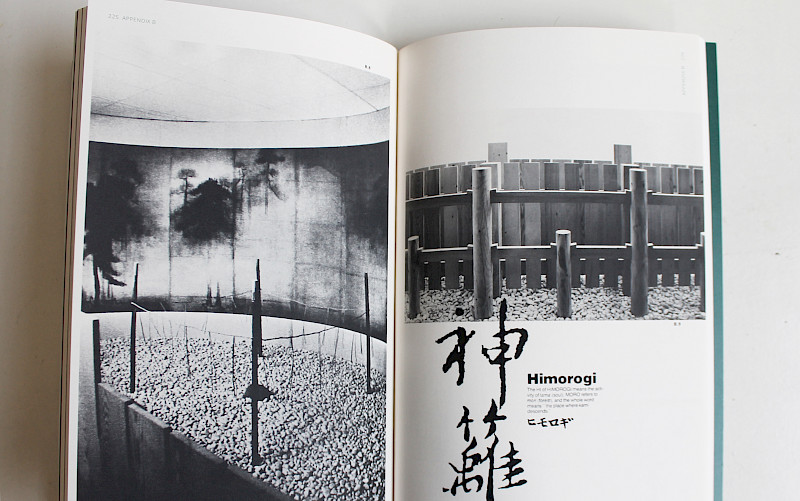

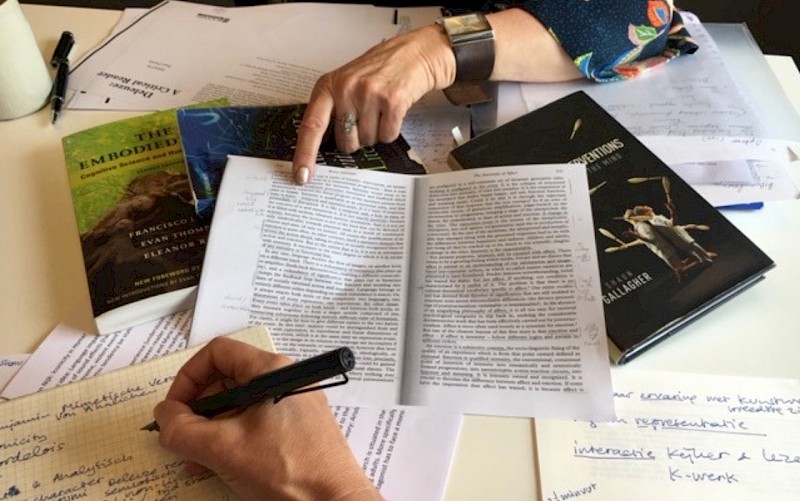

Much like the modern “language” of DNA, I have always been fascinated by early writing systems and our attempts at contemporary translation. Clay tablets unearthed from the ground, buried with the tardigrades and other underground critters, supposedly tell stories of ancient myths, love notes or document a grain stocktake. But are we sure? What if messages have been lost through time? What if they tell the impossible? And what if ancient artefacts dug up from the earth told stories of the tardigrades living there?

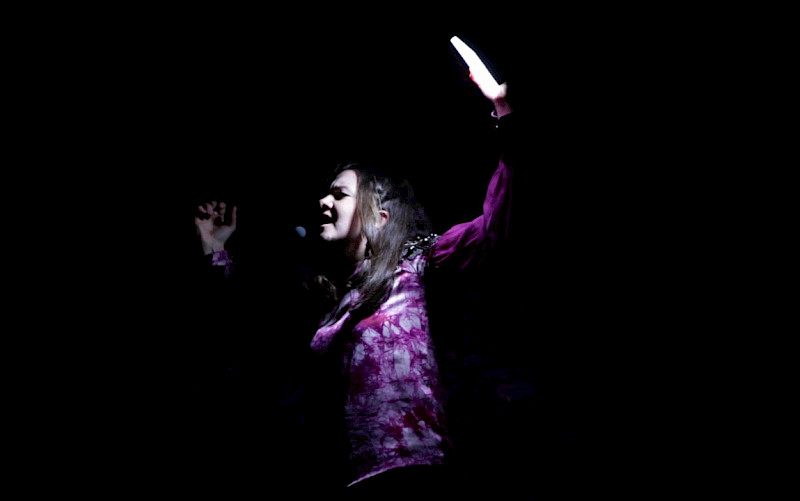

To pose these questions we chose to imagine one of the newest technologies and scientific languages — DNA — written in the earliest form of written language: cuneiform. We envisaged a clay tablet inscribed with a tardigrade DNA sequence, written in cuneiform. And this was the basis of our performance. The DNA sequence was translated to sound via an algorithmic software. SHOAL improvised alongside it with instruments and movements, making a kind of worship ritual for the tardigrades.

Sadly, like many things over the pandemic, we weren’t able to perform this live as planned. But, it sewed the seeds of a project that grew much beyond my initial expectations.

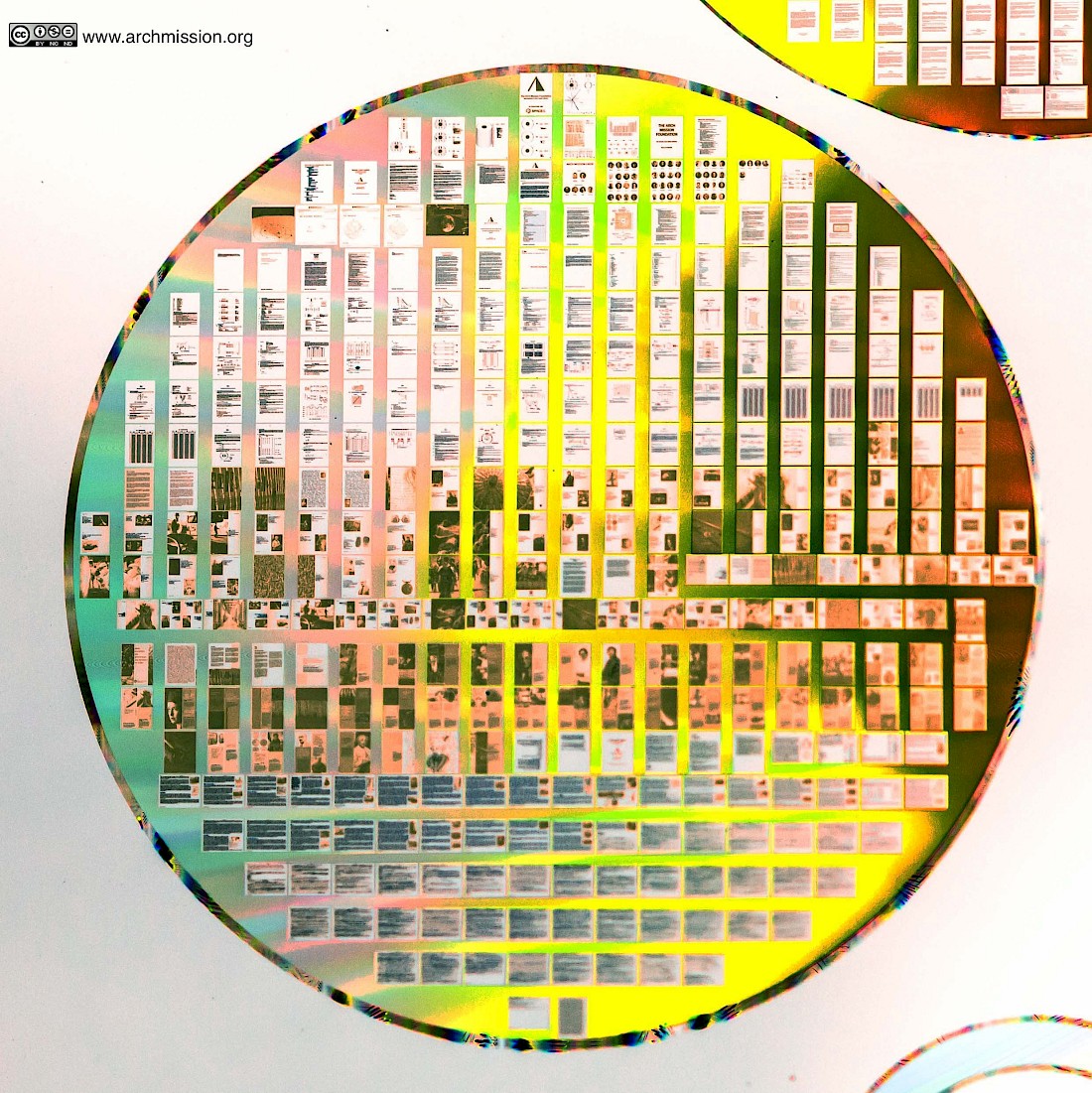

The Arch Lunar Library™

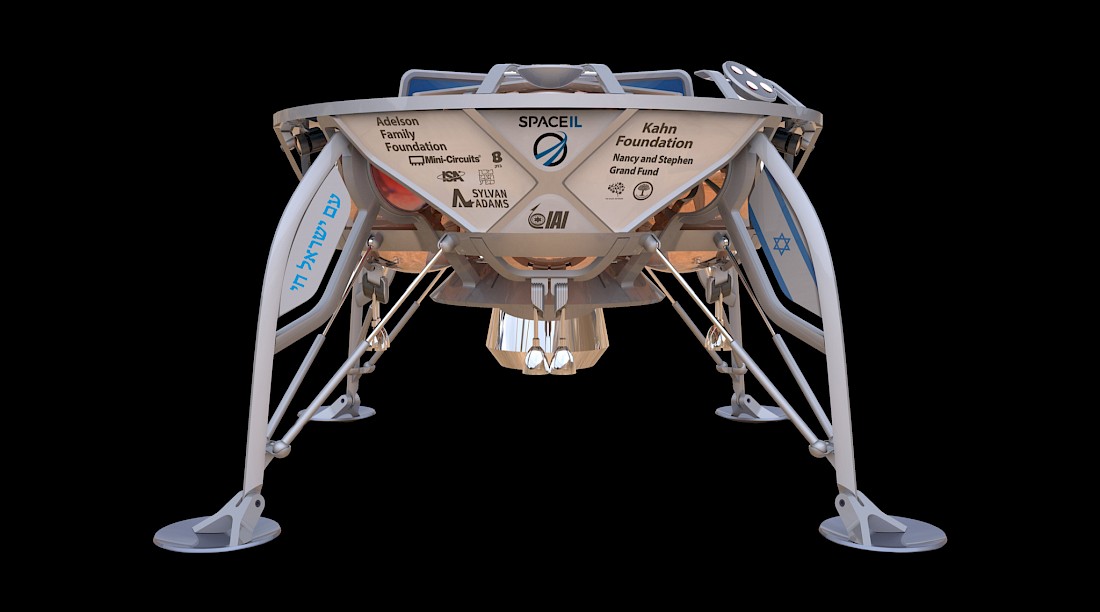

The catalyst for the growth of this project was the discovery of a rather peculiar story. Anyone who has Googled tardigrades since February 2019 has undoubtedly come across articles proclaiming that tardigrades live on the moon. For those of you not familiar with the event, I will give you the brief rundown. In 2019, Nova Spivak, a Buddhist, Israeli-American entrepreneur sent an archive of humanity — The Arch Lunar Library™ — on the world’s first privately funded space mission, by Israeli state space agency SpaceIL. This archive was placed onto a spacecraft that goes by the name of Beresheet, meaning ‘in the beginning’ in Hebrew.

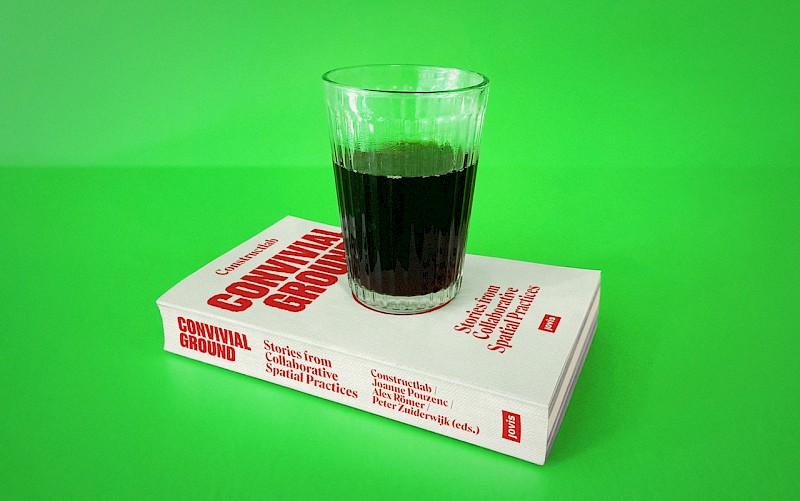

Constructed with nano-technology, the archive was a kind of microscopic library. Letters the size of bacillus bacteria are engraved into small thin sheets of metal, resembling CDs. These disks are piled on top of one another into a kind of tower, readable through a microscope. They are designed to last for billions of years and for future intelligent life to learn about humanity and planet Earth. Within this archive are a selection of the weird, wonderful and problematic. In the white paper made about the project, amongst other things you can find the following items listed:

- the entirety of English-language wikipedia

- David Copperfield’s magic secrets

- the history of Israel

- The Clock of the Long Now

And there are many more inclusions to be slowly revealed over time. Alongside this microscopic library was organic matter, including particles of earth from where Buddha supposedly gained enlightenment, human DNA, and, the thing that really piqued my attention: a colony thousands of tardigrades encased in artificial amber. In a podcast interview with Spivak, he claimed that the tardigrades were placed in his archive as a “poetic gesture”. Their ability to withstand atmospheric pressures of space in previous experiments meant that although there were in a desiccated, hibernation-like state, they would technically be “alive” in space.

However, not everything went to plan and in February 2019 Beresheet crash-landed on the moon into the Sea of Serenity. And so, tardigrades became the first terrestrial Earthling to be alive and resident of the moon.

Making (sense of) reality

Becoming mildly obsessed with these interstellar tardigrades, I dug deep into various forms of research. I collected images, I read the Arch Lunar Library™ white paper, I found a Google doc investigating the exact location of the space crash, I read articles about whether the tardigrades could possibly survive on the moon. Eventually, in the midst of this I wrote a story taking elements of the event which saw them crash on the moon, but translating them into a fairytale world. You could say that to make sense of the reality I formed a fantasy.

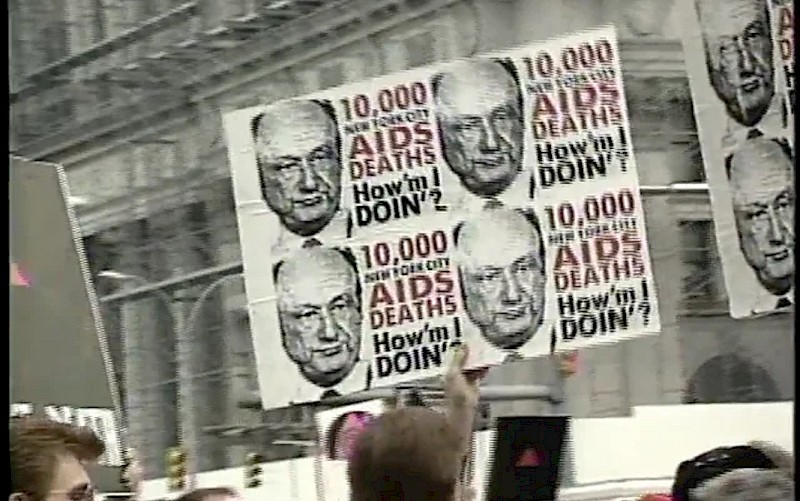

There were certain aspects that remained, for example some of the contents of the archive, name references or the location of the crash-landing being the Sea of Serenity. Yet there were certain aspects that I omitted or altered. Namely, the ties of the archive to Israel.

I struggled with the ethics around this decision. When I included an overt reference to a country with such problematic policies of expansionism and imperialism it became a loud political message. When I omitted it, I felt as though I was at worst stifling an oppressed voice, or at best hiding away from a contentious issue. But the Israel-Palestine war is not my story to tell, particularly in the form of a fairytale. My criticism here was not solely aimed at the Israeli policy of expanding borders, but of all countries, and of the human propensity to expand borders at large. Of trying to expand our presence beyond this planet into space. Of believing we are the most important species that must be preserved in time capsules for billions of years. And so I decided the most effective way to speak was in general terms, to keep everything on a separate, non-specific, fantasy plane. To let this reflect on reality, as opposed to try and document it.

After all, my intention was to rewrite the story of the tardigrades that are stuck on the moon into a tale where they come out on top. A story where the humans are the secondary characters. It could also be argued that this isn’t my story to tell, or to rewrite. But, tardigrades may have many unbelievable powers, they cannot currently speak in human tongues. And so I decided to try and be translator.

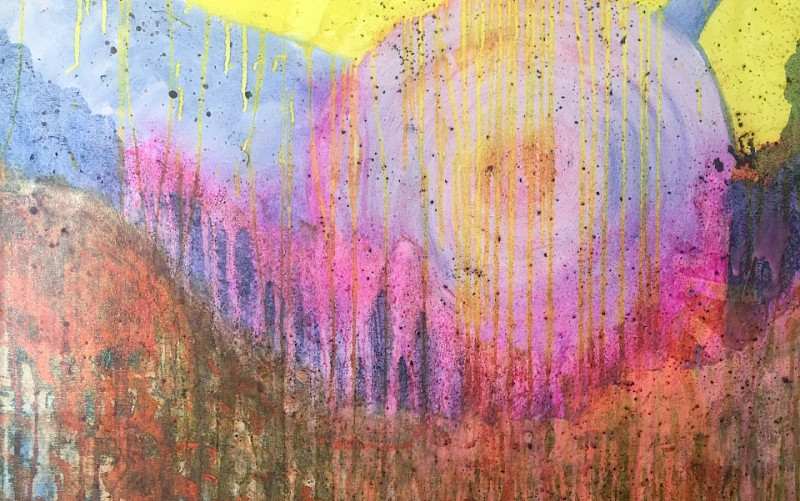

Simultaneously, I continue making material manifestations of certain aspects of the story; in a sense bringing them into reality. The largest of these is my giant moon: The Lunar Moss Piglets in the Sea of Serenity. In my story, In the beginning…, the crash-landing of the spacecraft bursts a spring of water on the moon which allows mosses to grow and tardigrades to thrive in their favourite habitat, moss. My intention by making this giant moon, as well as illustrating a moment from the story, was to offer a kind of reparative gesture for the tardigrades trapped on the moon. To create for them an optimal tardigrade ecosystem for their cousins still on Earth.

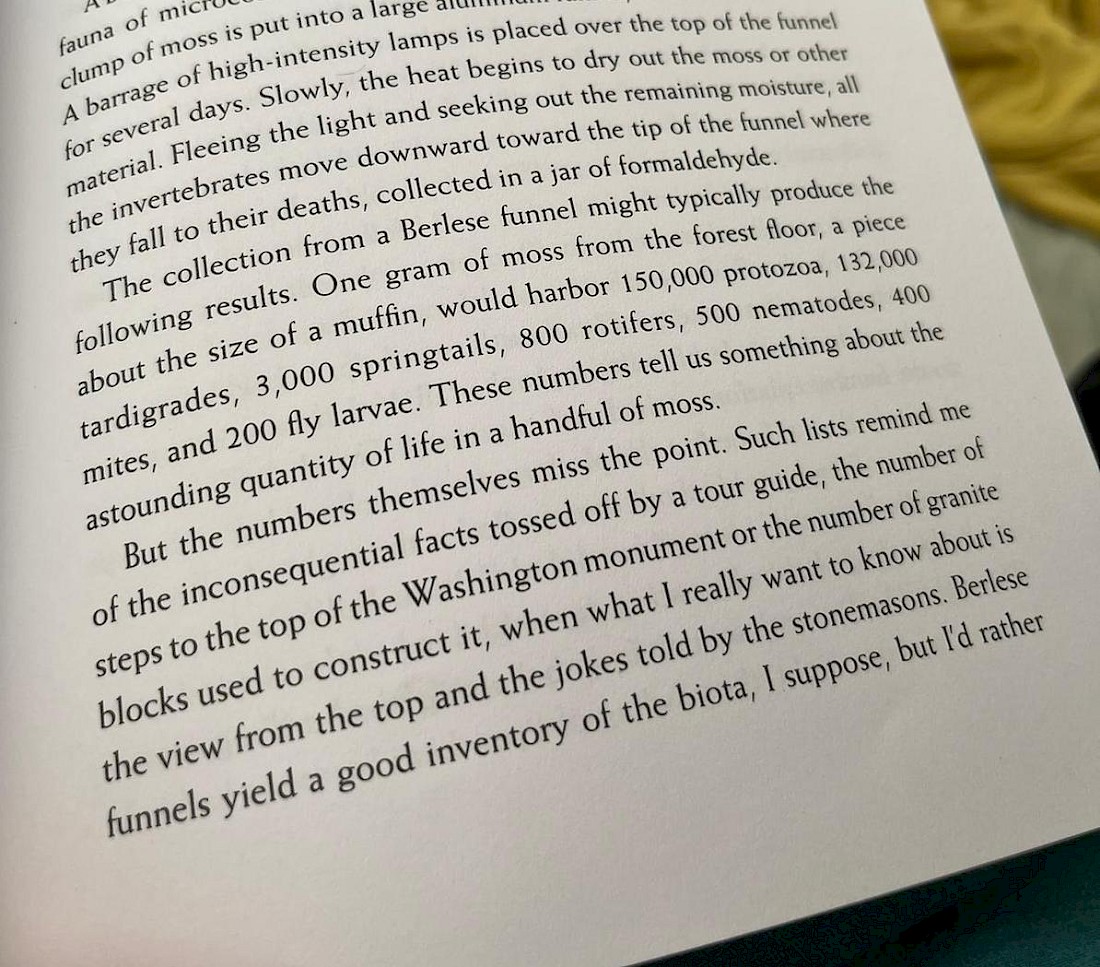

Making this optimal tardigrade ecosystem required me to work with living beings, animals and plants that are real and alive. Mosses and tardigrades, amongst all the other myriad, microscopic life forms found in just 1g of moss (see pic below) have become an art material, although I prefer to consider them my collaborators. Together, they have encouraged me to think about what it means to cultivate and care for something within an art practice, and to confront the reality in storytelling.