Schoenberg the Romantic

Performing Arnold Schoenberg’s early atonal piano music on period instruments

In 1981, the Royal Conservatoire (Koninklijk Conservatorium) in The Hague, the Netherlands, moved into a new building, an example of modernist architecture with influences of brutalism. At its entrance, a statue of Arnold Schoenberg was placed, made by sculptor Heppe de Moor. The monument consisted of three parts: a large block of marble outside, and inside the building two heavy constructions of epoxy resin – one in which the image of Schoenberg detached itself from the hard stone, as it were, and finally one in which Schoenberg appeared full-length. Schoenberg's figure was recessed as a cut-away inside the block of epoxy and was thus depicted in negative. This met the wish of the management at the time not to suggest ‘nineteenth-century hero worship’.

Nevertheless, Schönberg was indeed seen as nothing less than the founder of the Royal Conservatoire's self-image in those days. In the 1950s, Kees van Baaren became the first Dutch composer to apply the dodecaphonic technique, followed by his pupils, among whom Jan van Vlijmen. Both Van Baaren and Van Vlijmen were directors of the conservatory and from the 1970s onwards, a true Haagse School (Hague School) developed within its composition department – with Louis Andriessen perhaps as the most internationally acclaimed representative. In addition, the conservatory named its main concert hall in the new building after Schoenberg, and the institute was the cradle of the internationally active Schoenberg Ensemble, founded in 1974.

Despite the conscious anti-heroism, Schoenberg definitely appeared monumental in this statue. In the words of Reinbert de Leeuw, the leader of the Schoenberg Ensemble, the Royal Conservatoire honoured ‘the composer and pedagogue, who is still a symbol of the immortality of the art of this century, the man who brought about the breakdown of the principle of classical music’.

Forty years later already, the Royal Conservatoire again moved into a new building and the previous housing was pulled down. Heppe de Moor's monumental representation of the symbol of the immortality of modern art met a sad fate. After investigations by concerned former students and teachers of the conservatory it became clear that neither the conservatory itself, nor the new municipal cultural centre, nor other concert halls for new music or even the artist’s family, had been interested or able to give the sculpture a new place. During a last-minute attempt to save the statue by moving it to a depot, it collapsed and was heavily damaged – allegedly due to material fatigue.

The symbolic value of these events is hard to miss. The statue represented an image of Schoenberg that was in line with a teleological view on the history of modernism in music. This image was in the first place promoted by Schoenberg himself, but after his death, it met with enthusiastic approval in the environment of post-war serialism and the Darmstadt School. One might argue that in our days, this is a view on history that, just like the regretted monument, has been thrown out with the trash by many.

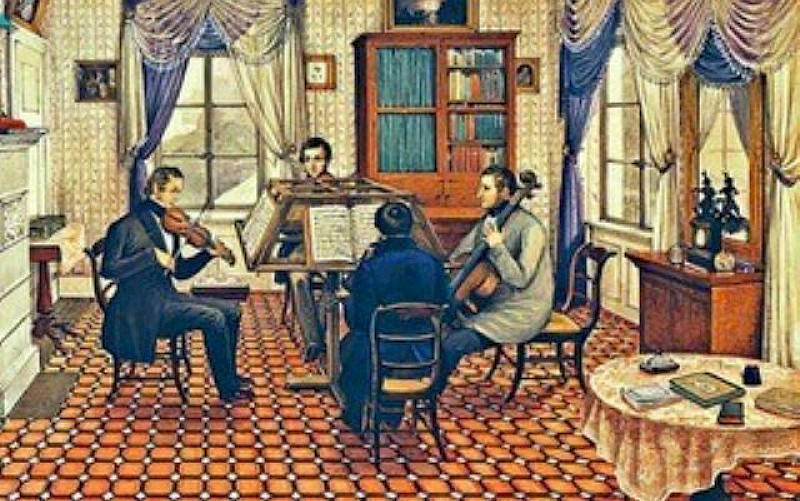

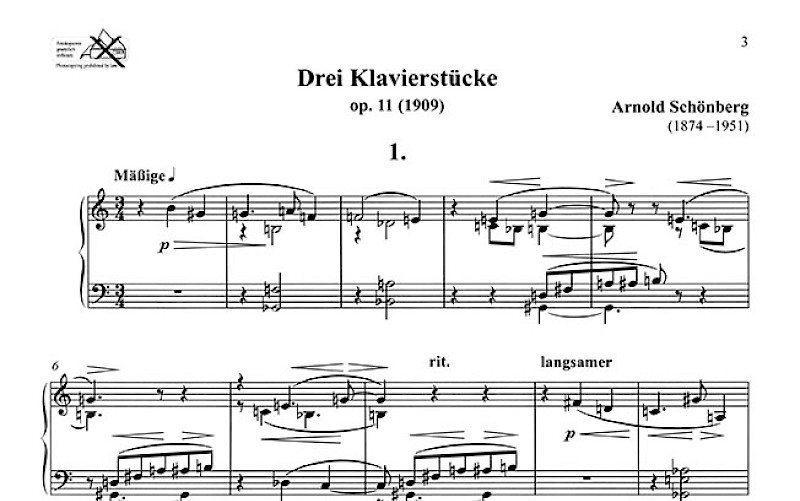

It is, however, just an image. Schoenberg depicted himself as the pioneer for the music of the future, the prophet whose own oeuvre both showed and initiated an inescapable and necessary development. If this image has lost much of its attraction nowadays – if alone because music has taken different courses – this opens up possibilities for different views. The idea of a continuous and goal-oriented development in his work has been questioned by many. The advantage of a non-teleological view is that it frees the earlier work from the ‘not-yet’ qualification. Schoenberg’s early atonal compositions, for instance, are not just a preparatory stage before the ‘real’ dodecaphonic works but represent a special world in its own right. Putting aside for a while our knowledge of what would follow in later years brings us closer to the ‘horizon’ of expressionistic works such as the 3 Klavierstücke op. 11 (1909) and the 6 kleine Klavierstücke op. 19 (1911). For Schoenberg’s music, no matter how innovative or even incomprehensible it may have seemed to contemporaries, appeared in a context. It was written for such contemporaries in the first place. How would pianists in Schoenberg’s time, shaped by works of composers such as Liszt, Brahms and Reger on the one hand, and by the pianos of their days on the other hand, read the scores of op. 11 and 19? This is the central question this article seeks to address. Not to make our performances ‘authentic’ in a way that will never be possible – but to broaden our own horizon, to be inspired by performative options that our time has forgotten about. In the words of music theorist Robert S. Hatten, ‘I simply contend that we should have a better idea of how such [historical] works could have been interpreted at the time of their creation, and that this is a necessary complement to the kinds of meanings they might have for us today, when we factor in the perspectives of all the styles, interpretive approaches, and ideological stances that have emerged or been constructed since their time’.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, the position of the music of Schoenberg and the Second Viennese School was undisputed thanks to the link with the modernism of Darmstadt and Donaueschingen. Nowadays, the popularity of serialism has waned, and it seems that Schoenberg’s music is being performed less as well. It would be good for our time not to look at the Second Viennese School through the lens of the modernists of half a century ago, but to develop a new relationship with what may now be considered early music. For this music deserves a longer life than crumbling stone or deteriorating epoxy.