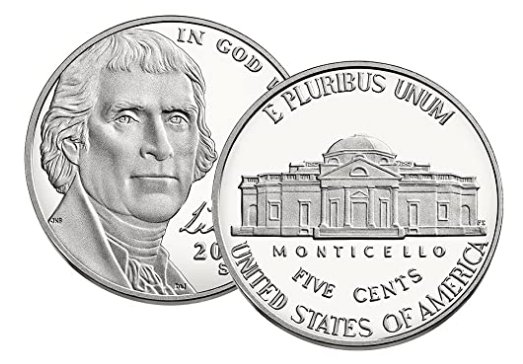

Musical Monticello: Classical Music and America

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello plantation is here used as a case-study examiningclassical music’s foundations in the United States. Among other titles, Jefferson was a statesman, diplomat, slave master, and avid violinist. He is remembered as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and third U.S. President. Early documentation suggests he was a gifted musician, reading notation at age nine and practicing “no less than three hours a day” for “a dozen years”. Music played an important role in the courtship of his wife, Martha Skelton Wayles, a harpsichordist and singer. They parented six children, of which two daughters survived to adulthood. Both received substantial keyboard training and their eldest inherited her father’s “taste and talent for music”. Upon their mother's death in 1782, Thomas began a complicated relationship with his late wife’s enslaved half sister, Sally Hemings. She became pregnant at sixteen and bore six of Jefferson’s children, four of which survived to adulthood. While Jefferson’s white daughters learned keyboard, two of his enslaved black sons were taught violin. It is likely that Jefferson himself taught them using the treatises of his expansive musical library, notably Geminani’s “Art of Playing the Violin”. A year after Jefferson’s death, the two sons were given their freedom; the youngest’s profession is listed as “musician” in the 1850 census; he is remembered as an “accomplished caller of dances”. These sons span the full stylistic gamut available in 19th century American music: from fiddle to violin. Thomas Jefferson and his family represent the kernels of America’s musical traditions, and the way they have morphed in parallel with America itself. The musical ecosystem of Monticello plantation is a dynamic location to discuss colonial music’s intersections with class, race, gender, and national identity.

Author: Jasper Snow