Testimony of participant Rahma Hamzi

For the past three years, Rahma Hamzi has been been participating in the Here/Then and Now research group. As a female and a Palestinian living and practicing outside the art world center, she wanted to do art that is more related to her as an individual and more related to her daily environment. She continues...

....I wanted a framework to talk, discuss and develop art and thoughts, which is something that is lacking me as an artist and as an individual living in Ir el Maksour, a small Bedouin village in the Northern District. It has a multilayered relationship with politics, religion, gender and personal space and freedom, maybe due to the fact that the vast majority of the people living in the village are derived from the same tribe. Combined with colonialism, occupation and patriarchy, tribalism had a strong effect on the social fabric. It appears to me that it has created a sense of a collective fear of being dissented from the majority, as well as a strong awareness of limitation.

In my previous artworks, in which I expressed my thoughts about this fear and boundaries through an aesthetic and visual centered process, but also very subdued and unobtrusive. Using themes from nature mostly, that represented the body, sexuality, sacrifice, purity, and impurity. At some point I started to realize that I was ignoring the sociopolitical noise in the background, and wanting to make art that is alert of the complexity and power relations that I encounter in my day-to-day life, that it is different from individual to another but has a shared base with people living around me as Palestinians. Questions of how art makes any difference, or how to make a living out of art, from where the money I get paid for doing art comes from and whether I even have an interest in being a part of the mainstream art world as it’s functioning today have occupied my mind.

The first year of the program was full of new experiences and encounters with varied ways of action in the art field. Still, I was more focused on responding to the place in which I exist and live in, rather than trying to integrate or change it. Thinking about power relations, restrictions, and control embedded in social construction as ways of living in this complex place we live in, especially in the village I come from, I did a performative action that relies on the participation of the spectators. In which, I arranged a minimal setup with bondage ropes, a table, and two chairs, see photo 1.

The interaction with people who came in was spontaneous and intuitive, so that actions started to take place when the first person asked about the ropes, unfolding a conversation about the history of Shibari, bondage usage in torture, healing and sexual practices. Any further interaction was based on the chemistry between me and the visitor. I was also trying to be sensitive while reading the person facing me, some people were comfortable letting me bind them, see photos 2 and 3, also then, I was trying to be more mindful of their “signals” and receptive to their energy. While others saw the whole action as weird and were hesitant and uncomfortable and chose not to participate or took a spectator position only.

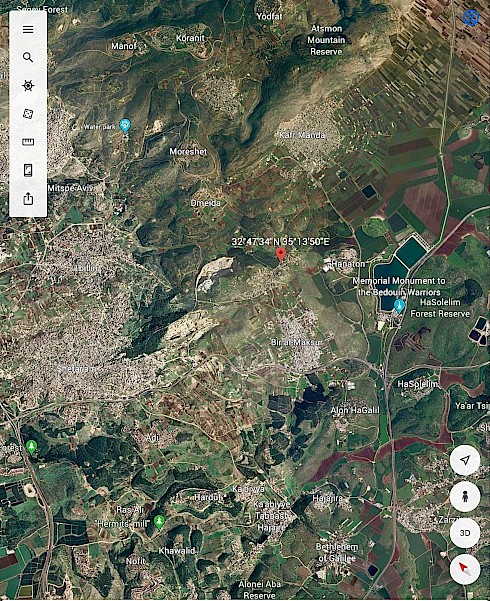

By the second year, I thought about how it is that any form of artistic action, done outside my environment, would only respond to it without making actual change. Thus, combined with the fact that interest in art practice among individuals in my surroundings is close to nothing and the shortage of socializing public spaces, I decided to make use of public woods in my neighborhood, in an attempt to merge that marginal space into ordinary daily activities, since individuals are very detached from public spaces. At that time, I had no historical or political background regarding the woods surrounding the village (on the below map you can see Bir el-Maksour and the neigbours. The red pin marks my neighorhood and the nearby forest.)

I remember being staggered, after I married and moved from another neighborhood to where I currently live, to see that people do not usually go in there, and I thought of how much these public places and nature are unappreciated and wasted. So what Saadah Juhaina, a member of Here and Now group, and I did was mostly a gathering spot in the woods and people who came in could hang around, talk and paint on white big canvases that we hang between the trees around the gathering place, photo of Valeria Gaslev below.

The gathering spot worked for that day as a socializing place where people who attended chatted and talked about different topics such as what could bring people together with the public space. And how the social dynamics, norms, and life-style are affected by economics, politics, cultural structure and the regime. The canvases we used served the people as a way to vent and express feelings and thoughts they had during or after the conversations, and they were left in the woods after the gathering ended as a trace, and people passing by could see them from the nearby street.

Through the third year, my interest in understanding how social and political factors shape the relationship between people and their surroundings had continued. Soon after the gathering at the woods in the village, I learned from a conversation with an elderly man from the neighborhood, that all of the forests in the region were planted by The Jewish National Fund, also more about the political story of the village, is that native people of Bir el Maksour were displaced from a nearby land in 1948. In the same conversation he told me that he remembers the gunshots as a 5 years old boy in 1948, but for some strange reason, the collective memory of the people of the village is very nostalgic regarding how they moved to live from one place to another.